13. Family Associations & the Chinese Six Companies

With his arrival in San Francisco in 1881, Dong Hin would soon become part of the incredibly complex business and societal organizations that effectively ran Chinatown. The fundamental building block of Chinese society has always been the family unit, through which social order was maintained. This basic tenet was no different for the earliest Chinese immigrants to America. As family or clan members arrived, they shared unique dialects, customs, and loyalties and thus would naturally band together as they began to create a new life in America. Often the center of this activity was in a merchandise store operated by one of the clan members. Once the store began to grow, the owner would send for more relatives or others with similar family-names from China to join the company. This mechanism of overlapping social and business “recruitment” would lead to the phenomenon of particular families controlling particular industries. Examples include our own family’s involvement in the worker’s garment industry; the Dear (also transliterated as Dea, Dere, Jear, Jay, etc) family’s control of fruit and candy stalls and stores; and the ownership of better class restaurants by the Yee’s and Lee’s.

As the immigrant population grew, a need arose for organizations to maintain social order. Unfortunately, because of the growing prejudice and hostility of Americans, the Chinese could not turn to the “American courts for settlement.” Instead, a complex set of social institutions evolved in Chinatown, designed to maintain order in the fledgling community.

Family Associations were created with membership based on the same surname. With the rising wave of immigration, family associations grew and eventually purchased buildings as headquarters for the group. The elders of the family associations were responsible for maintaining order within the association by settling disputes, helping the needy, and disciplining the unruly.

Further maintaining ties to their homeland, the Chinese of San Francisco established district associations based on one’s place of origin. In Chinese these associations were called 會館 or "huìgǔan," roughly translated as "organization/meeting" and "public building." Of the approximately 90 districts of Guangdung of the time, about twenty-four were heavily represented in Chinatown. Like the family associations, these district associations played a major role in keeping order in Chinatown. However, instead of focusing on individual disputes within clans, the district associations dealt with problems between businesses and groups or issues “between” districts.

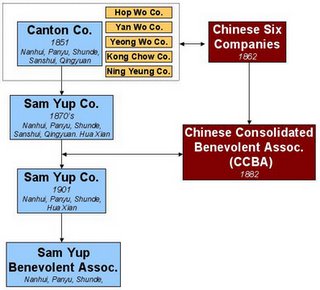

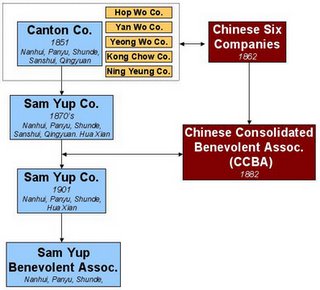

(1) The evolution of the Sam Yup Benevolent Association and its relationship to the "Chinese Six Companies" which would become the CCBA (adapted from the Chinese Historical Society of America).

(1) The evolution of the Sam Yup Benevolent Association and its relationship to the "Chinese Six Companies" which would become the CCBA (adapted from the Chinese Historical Society of America).

By about 1862, there were six major district associations: 1) our own Sam Yup (Canton Co.); 2) Kong Chow; 3) Ning Yeung; 4) Yeong Wo; 5) Hop Wo; and 6) Yan Wo. Seeing the need and realizing the advantage of combining power, these district associations joined together to form the “Chinese Six Companies.” This organization would remain the unchallenged supreme authority in Chinatown for more than 50 years. In 1901, the Six Companies was incorporated and officially became known as the “Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association” or “CCBA.”

(2a) The Sam Yup Benevolent Association building at 835 Grant Avenue; (2b) the doorway to the Sam Yup Association (photos, Steve, 2006).

(2a) The Sam Yup Benevolent Association building at 835 Grant Avenue; (2b) the doorway to the Sam Yup Association (photos, Steve, 2006).

It’s difficult to overstate the power of the “Chinese Six Companies.” At its peak, the “Six Companies” was empowered to speak on behalf of all Californian Chinese, was the “official board of arbitration for disputes between the various district groups,” and “before the establishment of any Chinese consular… agency in America, the Chinese Six Companies acted as spokesman for the Imperial Manchu government in its relations with the Chinese in America.”

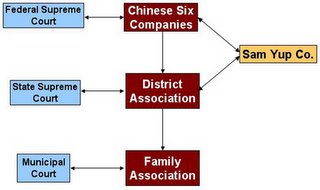

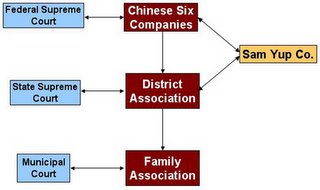

If you’re confused by all these groups, you’re not alone. Probably the handiest way of picturing this is to think of the way the American legal system is organized: 1) family associations are like municipal courts; 2) district associations serve the role of the state supreme court; and 3) the “Chinese Six Companies” was the final arbiter of all issues as is the federal supreme court.

(3) Legal and administrative hierarchy of various organizations with Chinatown. As a district association, the Sam Yup Co. dealt with matters internal to the district, but also had a major voice as a member of the Chinese Six Companies.

(3) Legal and administrative hierarchy of various organizations with Chinatown. As a district association, the Sam Yup Co. dealt with matters internal to the district, but also had a major voice as a member of the Chinese Six Companies.

Some of the “Chinese Six Companies” noteworthy accomplishments include maintaining a Chinese census, starting Chinese language schools, establishing the Chinese Hospital (particularly important since the Chinese could not be admitted to the San Francisco County Hospital during the 1860’s and 1870’s), and fighting all anti-Chinese legislation enacted by the City, state, and federal governments. However, there was a dark side to the power amassed by the “Six Companies.” The organization was effectively a nonvoluntary "voluntary association" – businessmen had to pay membership dues if they wished to stay in business. Additionally the Six Companies controlled movement back to China through the issuance of “exit permits.” The CCBA convinced steamship companies like the Pacific Mail Steamship Company not to sell tickets to Chinese who wished to return to China without an “exit permit.” Of course, a fee was associated with these permits, and the fee became an important "tax power” that would remain in place until the 1949 Communist takeover of China.

(4a) The CCBA building at 843 Stockton Street; (4b) CCBA letterhead; (4c) the door way to the CCBA; notice the last two characters to the left over the doorway: 會館 or "huìgǔan (photos, Steve, 2006).

(4a) The CCBA building at 843 Stockton Street; (4b) CCBA letterhead; (4c) the door way to the CCBA; notice the last two characters to the left over the doorway: 會館 or "huìgǔan (photos, Steve, 2006).

The CCBA still exists today, its headquarters located at 843 Stockton Street at Clay (by the post office). Though still somewhat a secretive institution, its aspirations and history are readily apparent in the wording on its letterhead:

“The Official Representative Association of Chinese in America”

Links

A History of the Chinese in California: A Syllabus, Thomas Chin (ed)

"Chinatown Introduction: a Tale of Four Cities," Randolph Delehanty

As the immigrant population grew, a need arose for organizations to maintain social order. Unfortunately, because of the growing prejudice and hostility of Americans, the Chinese could not turn to the “American courts for settlement.” Instead, a complex set of social institutions evolved in Chinatown, designed to maintain order in the fledgling community.

Family Associations were created with membership based on the same surname. With the rising wave of immigration, family associations grew and eventually purchased buildings as headquarters for the group. The elders of the family associations were responsible for maintaining order within the association by settling disputes, helping the needy, and disciplining the unruly.

Further maintaining ties to their homeland, the Chinese of San Francisco established district associations based on one’s place of origin. In Chinese these associations were called 會館 or "huìgǔan," roughly translated as "organization/meeting" and "public building." Of the approximately 90 districts of Guangdung of the time, about twenty-four were heavily represented in Chinatown. Like the family associations, these district associations played a major role in keeping order in Chinatown. However, instead of focusing on individual disputes within clans, the district associations dealt with problems between businesses and groups or issues “between” districts.

(1) The evolution of the Sam Yup Benevolent Association and its relationship to the "Chinese Six Companies" which would become the CCBA (adapted from the Chinese Historical Society of America).

(1) The evolution of the Sam Yup Benevolent Association and its relationship to the "Chinese Six Companies" which would become the CCBA (adapted from the Chinese Historical Society of America).By about 1862, there were six major district associations: 1) our own Sam Yup (Canton Co.); 2) Kong Chow; 3) Ning Yeung; 4) Yeong Wo; 5) Hop Wo; and 6) Yan Wo. Seeing the need and realizing the advantage of combining power, these district associations joined together to form the “Chinese Six Companies.” This organization would remain the unchallenged supreme authority in Chinatown for more than 50 years. In 1901, the Six Companies was incorporated and officially became known as the “Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association” or “CCBA.”

(2a) The Sam Yup Benevolent Association building at 835 Grant Avenue; (2b) the doorway to the Sam Yup Association (photos, Steve, 2006).

(2a) The Sam Yup Benevolent Association building at 835 Grant Avenue; (2b) the doorway to the Sam Yup Association (photos, Steve, 2006).It’s difficult to overstate the power of the “Chinese Six Companies.” At its peak, the “Six Companies” was empowered to speak on behalf of all Californian Chinese, was the “official board of arbitration for disputes between the various district groups,” and “before the establishment of any Chinese consular… agency in America, the Chinese Six Companies acted as spokesman for the Imperial Manchu government in its relations with the Chinese in America.”

If you’re confused by all these groups, you’re not alone. Probably the handiest way of picturing this is to think of the way the American legal system is organized: 1) family associations are like municipal courts; 2) district associations serve the role of the state supreme court; and 3) the “Chinese Six Companies” was the final arbiter of all issues as is the federal supreme court.

(3) Legal and administrative hierarchy of various organizations with Chinatown. As a district association, the Sam Yup Co. dealt with matters internal to the district, but also had a major voice as a member of the Chinese Six Companies.

(3) Legal and administrative hierarchy of various organizations with Chinatown. As a district association, the Sam Yup Co. dealt with matters internal to the district, but also had a major voice as a member of the Chinese Six Companies.Some of the “Chinese Six Companies” noteworthy accomplishments include maintaining a Chinese census, starting Chinese language schools, establishing the Chinese Hospital (particularly important since the Chinese could not be admitted to the San Francisco County Hospital during the 1860’s and 1870’s), and fighting all anti-Chinese legislation enacted by the City, state, and federal governments. However, there was a dark side to the power amassed by the “Six Companies.” The organization was effectively a nonvoluntary "voluntary association" – businessmen had to pay membership dues if they wished to stay in business. Additionally the Six Companies controlled movement back to China through the issuance of “exit permits.” The CCBA convinced steamship companies like the Pacific Mail Steamship Company not to sell tickets to Chinese who wished to return to China without an “exit permit.” Of course, a fee was associated with these permits, and the fee became an important "tax power” that would remain in place until the 1949 Communist takeover of China.

(4a) The CCBA building at 843 Stockton Street; (4b) CCBA letterhead; (4c) the door way to the CCBA; notice the last two characters to the left over the doorway: 會館 or "huìgǔan (photos, Steve, 2006).

(4a) The CCBA building at 843 Stockton Street; (4b) CCBA letterhead; (4c) the door way to the CCBA; notice the last two characters to the left over the doorway: 會館 or "huìgǔan (photos, Steve, 2006).The CCBA still exists today, its headquarters located at 843 Stockton Street at Clay (by the post office). Though still somewhat a secretive institution, its aspirations and history are readily apparent in the wording on its letterhead:

“The Official Representative Association of Chinese in America”

Links

A History of the Chinese in California: A Syllabus, Thomas Chin (ed)

"Chinatown Introduction: a Tale of Four Cities," Randolph Delehanty

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home