12. Arrival

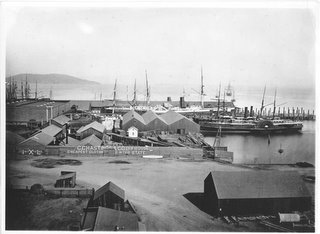

a trans-Pacific crossing was always a dramatic affair. We can imagine that Dong Hin, aboard the Pacific Mail Steamship "City of Peking," observed a spectacle much like that described by Albert Evans in 1869 in the Atlantic Monthly as the ship made her approach for the Pacific Mail Steamship dock located at 1st and Brannan Streets (Figure 1, circa 1875, San Francisco History Center). Evans wrote:

a trans-Pacific crossing was always a dramatic affair. We can imagine that Dong Hin, aboard the Pacific Mail Steamship "City of Peking," observed a spectacle much like that described by Albert Evans in 1869 in the Atlantic Monthly as the ship made her approach for the Pacific Mail Steamship dock located at 1st and Brannan Streets (Figure 1, circa 1875, San Francisco History Center). Evans wrote:"[The ship rounds] Rincon Point, and is laying in the stream, off the southern end of the wharf, with hawsers out, vainly endeavoring, against the strong ebb tide, to warp into her berth on the western side. The bow hawser parts at last, and she drfits out towards Yerba Buena Island, then swings slowly around under steam, heads toward San Jose, and then, when about half a mile away, turns gracefully, and with her monster wheels beating the bay into foam, comes rushing at full speed directly down toward the wharf... The monster of the deep obeys her helm to perfection, comes swiftly into her berth right alongside the wharf, and before we have ceased wondering at the immense proportions of this magnificent specimen of American marine architecture, her wheels are reversed, and she has ceased to move."

Welcome to San Francisco!

Continuing with Evan's evocative 1869 description:

"Then, for the first time, we observe that her main deck is packed with Chinamen - every foot of space being occupied by them - who are gazing in silent wonder at the new land whose fame had reached them beyond the seas, and whose riches these stalwart representatives of the toiling millions of Asia have come to develop. The great gangway-planks... are run out from the wharf and hoisted into place... [and] the custom-house officers ascend to the decks, the detectives and policemen range themselves at the gangways fore and aft... The forward gangway is reverved for the diembarkation of Chinamen exclusively; the after gangway is for the cabin passengers, mostly Americans and Europeans."

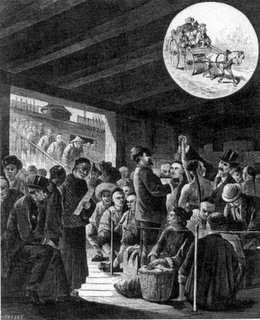

In those early years before the Exclusion Act of 1882 (more on this later), Chinese immigrants could pretty much come and go freely. As immigrant Huie Kin noted "in those days there were no immigration laws or tedious examinations." This relatively unrestricted movement was reflected in the number of Chinese immigrants coming into the US and San Francisco (see figure 2). Between 1860 and 1880, the Chinese population tripled to nearly 100,000. Only later, as enforcement of the Exclusion Act began, would severe immigration restrictions be set in place and would an immigration station be established in an old two-story shed at the Pacific Mail Steamship Company wharf. The more infamous immigration station on  (2) Cartoon showing the influx of Chinese immigrants into San Francisco from the Pacific Mail Steamship Company (on the left) and from Canada (on the right). Note the overalls building in the middle-left (18--, Bancroft Library, U.C. Berkeley).

(2) Cartoon showing the influx of Chinese immigrants into San Francisco from the Pacific Mail Steamship Company (on the left) and from Canada (on the right). Note the overalls building in the middle-left (18--, Bancroft Library, U.C. Berkeley).

After the cabin passengers disembarked, Evans wrote that a "living stream of the blue-coated men of Asia, bearing long bamboo poles across their shoulders, from which depend packages of bedding,  matting, clothing, and things of which we know neither the names nor the uses, pours down the plank the moment that the word is given, 'All ready!'...

matting, clothing, and things of which we know neither the names nor the uses, pours down the plank the moment that the word is given, 'All ready!'...

...As they come down upon the wharf, they separate into messes or gangs of ten, twenty, or thirty each, and, being recognized through some (to us) incomprehensible freemasonry system of signs by the agents of the 'Six Companies' as they come, are assigned places on the long, broad-shedded wharf... Each man carries on his shoulders, or in his hands, his entire earthly possessions, and few are overloaded. There are no merchants or business men among them, all being of the coolie or laboring class... There is a babel of uncouth cries and harsh discordant yells, accompanied by whimsically energetic gestures and convulsive facial distortions, as the members of the different gangs recognize each other in the crowd, and search out the places assigned to them."

From the perspective of a Chinese immigrant, Huie Kin recalled,

"[somebody] had brought to the pier large wagons for us. Out of the general babble, someone called out in our local dialect, and, like sheep recognizing the voice only, we blindly followed, and soon were piling into one of the waiting wagons… The wagon made its way heavily over the cobblestones, turned some corners, ascended a steep climb, and stopped at a kind of clubhouse, where we spent the night.”

I think Albert Evans displayed amazing insight into the significance of the Chinese immigrants' arrival in San Francisco. He concluded his 1869 article saying:

"We had indeed stood on the farther shore of the New World, and seen the human tides which have surged around the globe from opposite directions meet and commingle... It was a sight worth living long and coming far to look upon - a scene to wonder at, to ponder over and reflect upon - to gaze upon once and remember through all the coming years of life - a scene such as our fathers never beheld nor dreamed of, and of which our children's children only may know the full import and meaning."

Links:

The Chinese in California, 1850-1925, Bancroft Library, U.C. Berekeley

"Steamer from China" in More San Francisco Memoirs, 1852-1899 , Malcolm E. Barker (ed)

A History of the Chinese in California: A Syllabus, Thomas Chin (ed)

The Chinese American Album by Dorothy & Thomas Hoobler

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home