6. Loo Jow, then

Our family can trace itself back to Loo Jow (Lù Zhōu,

The various families lived in a small collection of family compounds made up of simple brick buildings. There were certainly none of the conveniences we take for granted today like paved roads, indoor plumbing, or electricity. Water was probably collected from canals carrying water from the nearby river and water buffaloes provided the primary means to tend crops. A commonly held view of this period suggests that most residents were probably subsistence farmers scrapping out meager existences. Thus, the general perception of emigrants from 19th century China is that of peasant farmers escaping poverty and hunger.

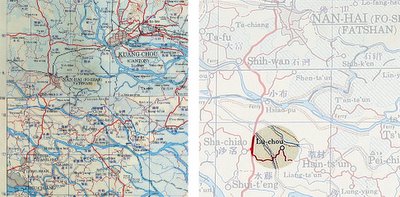

The various families lived in a small collection of family compounds made up of simple brick buildings. There were certainly none of the conveniences we take for granted today like paved roads, indoor plumbing, or electricity. Water was probably collected from canals carrying water from the nearby river and water buffaloes provided the primary means to tend crops. A commonly held view of this period suggests that most residents were probably subsistence farmers scrapping out meager existences. Thus, the general perception of emigrants from 19th century China is that of peasant farmers escaping poverty and hunger. (1a) AMS map of Shunde district (circa 1944, G7820 s250.U52 Case D nos. 78 & 84, U.C. Berkeley); (1b) highlighted location of Loo Jow (Lu-chou) (U.C. Berkeley).

(1a) AMS map of Shunde district (circa 1944, G7820 s250.U52 Case D nos. 78 & 84, U.C. Berkeley); (1b) highlighted location of Loo Jow (Lu-chou) (U.C. Berkeley).However, contemporary scholarship now suggests that much of this “perception” derived from anti-Chinese attitudes and propaganda in the United States that sought to cast Chinese immigrants as coming from the lowest social classes. On the contrary, much evidence exists that suggests Chinese emigrants, particularly from Shunde and the other Sam Yup districts, came from regions of relative prosperity. The Shunde district gazetteer estimated that “less than half of the population was engaged in solely producing grain.” Instead of focusing on “mere subsistence crops,” Shunde became a major commodities center, producing silk, fruit (like longans, lichees, and oranges), and fish.

To support their substantial role in domestic and international trade, the people of Shunde developed the commercial infrastructure required of such an expansive market economy. In 1853, the district gazetteer estimated that “60% of the people in Shunde worked in the fields, 20% were artisans, and the remaining 20% were in commerce.” As a consequence of this tradition of commerce and their market driven economy, emigrants from Shunde and the other Sam Yup districts were generally more likely to become merchants when they emigrated to the United States than Chinese from other regions of China. One might say that business was in the blood of people from Shunde.

Links

U.C. Berkeley, Earth Sciences & Map Library

U.S. Army Map Service (AMS, U.C. Berkeley)

Chinese San Francisco, 1850-1943 by Yong Chen

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home