15. Old Chinatown - "Tangrenbu"

1a) Ross Alley viewed from Jackson Street; (1b) "Pigtail parade" (Arnold Genthe, 1895-1906).

1a) Ross Alley viewed from Jackson Street; (1b) "Pigtail parade" (Arnold Genthe, 1895-1906).Upon arriving at "Dabu," the Cantonese name for San Francisco meaning "big city " or the "first city," Chinese immigrants made their way to the City's Chinese quarter known as "Tangrenbu" (Tong Yen Fau, "port of the people of Tang [i.e. Chinese]"). There had been a Chinese presence in Yerba Buena as early as 1838. As the village grew into the City of San Francisco, the Chinese presence grew concomitantly as waves of Chinese immigrants arrived, first in response to the gold rush and later as labor for the building of the transcontinantal railroad.

Chinatown first sprang up as a collection of Chinese stores on Sacramento Street (as known as "Tangrenjie" or Tong Yen Gaai, "the street of the Chinese People") between Kearny and Dupont (now Grant Avenue). The neighborhood rapidly expanded to a ten block area bordered by Broadway to the north, Kearny Street to the east, California Street to the south, and Stockton Street to the west (figure 2). As anti-Chinese sentiment grew in the mid to late 19th century, the life of Chinese immigrants would largely become restricted to the confines of the growing ghetto.

2) Map of Old Chinatown commisioned by the San Francisco Board of Supervisor's Special Committee on Chinatown. The color coding indicated the locations of "Chinese occupancy, Chinese gambling houses, Chinese prostitution, Chinese opium resorts, Chinese joss houses, and White prostitution" (circa 1885, Library of Congress).

2) Map of Old Chinatown commisioned by the San Francisco Board of Supervisor's Special Committee on Chinatown. The color coding indicated the locations of "Chinese occupancy, Chinese gambling houses, Chinese prostitution, Chinese opium resorts, Chinese joss houses, and White prostitution" (circa 1885, Library of Congress).There are few surviving documents that capture life in Tangrenbu during the late 19th century. Fortunately, what does remain are the photographs of Arnold Genthe (figure 1), a German tutor who came to San Francisco in 1895. Fascinated by Chinatown, Genthe taught himself the then-fledgling art of photography and spent the next decade photographing daily life in Tangrenbu. To get a glimse of old Chinatown, I cannot recommend enough the book "Genthe's Photographs of San Francisco's Old Chinatown" with historical context provided by John Kuo Wei Tchen.

As one can gather from the map in figure 2, old Chinatown was a complex neighborhood, very much male-dominated and defined in many ways by the forces of anti-Chinese attitudes. Thus it

is no surprise that Chinatown developed a certain reputation for lawlessness and vice. One of the most fascinating descriptions of old Chinatown I have come across is by former San Francisco Chief of Police Jesse B. Cook. He began as a beat officer with the SFPD, and later served as a sergeant with the “Chinatown Squad," a special unit formed in the 1880's to combat "vice" in Chinatown. In a June 1931 article in the San Francisco Police and Peace Officers’ Journal, Chief Cook described the conditions in San Francisco’s Chinatown before 1906 from his perspective as a member of the “Chinatown Squad.” Here are some selected exerpts from Cook's article, some of which focus on some of the shadier aspects of life in old Chinatown:

is no surprise that Chinatown developed a certain reputation for lawlessness and vice. One of the most fascinating descriptions of old Chinatown I have come across is by former San Francisco Chief of Police Jesse B. Cook. He began as a beat officer with the SFPD, and later served as a sergeant with the “Chinatown Squad," a special unit formed in the 1880's to combat "vice" in Chinatown. In a June 1931 article in the San Francisco Police and Peace Officers’ Journal, Chief Cook described the conditions in San Francisco’s Chinatown before 1906 from his perspective as a member of the “Chinatown Squad.” Here are some selected exerpts from Cook's article, some of which focus on some of the shadier aspects of life in old Chinatown: On Chinese names for the area:

"The State of California was at one time called “Gow Kum Shain,” or Old Gold Mill. Sacramento was known as the “second city,” or Yee Fow, and San Francisco had the Chinese name of Tie Fow, or “the big city.” America, that is the United States of America, was known as May Yee Kwock, or Ah May Yee Kah, also Fah Kay Kwock, meaning the flower flag country. Americans were known as Fah Kay Yen, or flower flagmen.

The Chinese had their own names for the alleys in Chinatown. The main streets, outside of Sacramento Street, were always known to the Chinese by their English names, the other streets, however, were all known by Chinese names.

If you asked a Chinaman where an alley was and gave the American name, he would be unable to tell you, for he would not know. But if you gave him the Chinese name, he would know immediately. For instance, Sacramento Street was known as China Street—in Chinese as Tong Yen Guy. The Spanish originally settled Ross Alley, but when the Chinese came they crowded the Spaniards out. This alley was, therefore, given the name of Gow Louie Sun Hong, or Old Spanish Alley. Spofford Alley was another alley from which the Spaniards were crowded out; this was called Sun Louie Sun Hong, or new Spanish Alley.

Alongside the old First Baptist Church, on Washington below Stockton was an alley, at the end of which was a stable for horses. The Chinese named this Mah Fong Hong, “stable alley.” A small alley off of Ross Alley was known as On New Hong, in other words, “urinating alley,” as the Chinese made it a regular urinating place.

Duncan [Duncombe] Alley is off Jackson Street, below Stockton, and is known as Fay Chie Hong, or “Fat Boy Alley.” This was named after a young boy living on the street who, at fifteen years, weighed about 240 pounds. A little way below, on the opposite side of the street, was St. Louis Alley. In the early days of Chinatown there was a large fire in the alley, which burned up quite a number of houses. The Chinese, therefore, called it “fire alley,” or “Fo Sue Hong.”

Opposite Fire Alley was Sullivan Alley, running halfway through from Jackson to Pacific Street. As there was a restaurant in this alley, the Chinese called it “Cum Cook Yen,” the same name as the restaurant.

Another alley was named “Min Pow Hong,” or bread alley, because there was a bakery on it. Brenham Place, running from Washington Street to Clay Street, back of the square, was called “Fah Yeun Guy,” or Flower Street, because of the park. Bartlett Alley, running from Jackson to Pacific Street, just below Grant Avenue, or Dupont Street, was called “Buck Wa John Guy,” or the grocery man who speaks Chinese. Opposite this was Washington Alley, known to the whites as “Fish Alley.” The Chinese, however, called it “Tuck Wo Guy,” after a store on it.

Waverly Place, originally known as Pike Street, ran from Washington Street to Sacramento Street, above Dupont, and was called “Ten How Mue Guy,” after a Chinese Temple in that street."

On Chinese boys and school:"The boys were sent to school; that is, to the Chinese school; they were not allowed to go to the European school. At that time there was one public school of about four rooms, on Clay Street, between Stockton and Powell Streets, those in attendance being mostly Japanese and other races. The Chinese boys went to their own school, from 8 o’clock in the morning until 10:30 at night, with time off for lunch and dinner. In Chinese, each character represents a word, and the only way they had of studying was to memorize these characters, which were placed on a blackboard or hung upon the wall. These were repeated over and over continually all day long until thoroughly imbedded in the minds of the boys. The teachers generally carried a long rattan and were very strict. If a boy made a mistake in reading from a chart, the teacher would hit him over the head with the rattan."

On the vices of Chinatown:

"People, generally, have the idea that Chinese are natural gamblers. This is not true. The old-time Chinese visited gambling houses so much because there were so few places of entertainment. In the first place, very few of them were married men. They could not speak English and, therefore, could not enjoy American dramas, dances or games. The only things left for them to do were either to visit houses of prostitution, gambling houses, lottery houses or the Chinese Theatre."

On fan tan gambling houses:

"In regard to the gambling games in Chinatown—my first trip to Chinatown was in 1889 as a patrolman in a squad. At that time there were about 62 lottery agents, 50 fan tan games and eight lottery drawings in Chinatown. In the 50 fan tan gambling houses the tables numbered from one to 24, according to the size of the room.

The game was played around a table about 10 feet long, 4 feet high and 4 feet wide. On this table was a mat covering the whole top. In the center of the mat was a diagram of a 12-inch square, each corner being numbered in Chinese characters, 1, 2, 3 and 4.

At the head of the table sat a lookout or gamekeeper. At the side was the dealer. This man had a Chinese bowl and a long bamboo stick with a curve at the end, like a hook. In front of him, fastened to the table, was a bag containing black and white buttons. He would scoop down into the sack with his bowl and raise it, turning it upside down on the table. The betting would then start.

After the bets were made, the dealer would raise the bowl and start to draw down the buttons, drawing four buttons at a time. The Chinese would make their bets at the drawing down of the buttons. The dealer would draw down until one, two, three or even four buttons would be left. Sometimes the Chinese would bet that the last four buttons would be all white, all black or that there would be a mixture of black and white buttons."

On lottery drawings (a game similar to keno):

"The Chinese have a very large room, with the doors constructed the same as in the case of a fan tan game room. The far end of the room is partitioned off with wire screens to the full width and about 8 feet deep. In back of the screen are two shelves, one of which acts as a counter for four Chinamen. Each Chinaman has a separate window in the screen. On the other shelf are placed Chinese ink pots and brushes, for the purpose of marking Chinese lottery tickets. Every Chinese lottery ticket has 80 characters on it, 40 above the line and 40 below. Each company stamps their own name at the head of the ticket. These tickets are really a Chinese poem, written by a Chinaman while in prison, and later adopted as a Chinese lottery ticket. There is not a thing on these tickets to designate their real use, although they are never used for any other purpose.

The agents around town had their offices in back of stores where they sell the tickets. Just before the drawing takes place, they present a triplicate copy of each ticket sold to the Chinaman at the window. The duplicate ticket is given to the purchaser, while the agent retains the original. As soon as all the money and tickets are in, the tickets are closed and the lottery is held.

In a little package, about 2 inches square, are 80 slips of paper. On each of these slips is a character corresponding to one of the characters on the lottery ticket. The Chinaman sets in front of him a large pan, like the old-time milk pans we used to set for milk to raise cream, and four bowls, each bearing a Chinese number—either 1, 2, 3 or 4. The small slips of paper are folded into little pellets, thrown into the pan and shaken up. The drawing then begins. The first pellet drawn is put into bowl No. 1, the next into bowl No. 2, and so on, until there are twenty pellets in each bowl.

The Chinaman then takes another small package, containing four little square pieces of paper. On each of these pieces is a figure in Chinese corresponding with the figures on the bowls. The same procedure is then followed as with the pellets. The slip picked from the pan is handed to the clerk, who in turn hands it to a man standing on the shelf in back of him. It is opened, in the presence of everybody gathered there. Of course, the bowl bearing the same number is considered the winning bowl; the other three are placed under the counter.

The pellets are then taken from the winning bowl and are pasted on a board in full view. These are winning characters. The Chinese mark the tickets by daubing the characters that agree with the ones on the board, with a brush. After this has been done, they present their tickets, and come back at the proper time to get their reward; that is, whatever they won."

On tongs and tong wars:

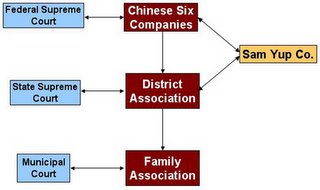

"We now come to the starting of the so-called “tongs,” commonly known as the “hi-binders.” The first tong was the Chee Kung Tong. Every man coming from China became a member of this tong. It was never known to have been in any trouble, for the Six Companies looked after the Chinese and saw that they were properly cared for.

In the early days, a Chinaman known as “Little Pete,” whose Chinese name was Fong Jing Tong, was interested in quite a number of slave dens, gambling places and lottery houses. The hoodlum element of Chinatown would make raids on these places and demand tribute money, or blackmail. It became so bad that Little Pete conceived the idea of forming tongs to protect his interests. The first tongs he started were the Bo Sin Sere and the Guy Sin Sere, and they guaranteed him absolute protection.

About this time there was another Chinaman, Chin Ten Sing, known as “Big Jim,” who also had large interests in a great many gambling, lottery and slave houses. He saw the protection that Little Pete was getting, and as he had to turn to his own houses for protection, decided to start some tongs also. Among them were the Suey Singsa, the Hop Sings and a number of others.

This proved very successful until the tongs started fighting among themselves over slave girls and gambling games. These wars sometimes lasted for several months.

During my first term in Chinatown in 1889, the Chinese did not use revolvers in their tong wars, believing they made too much noise. A lather’s hatchet sharpened to a razor edge was their chief weapon. With this they could chop a man all to pieces and generally, when they did leave him, would drive the hatchet into his skull and leave it there. The men using these weapons were known as Poo Tow Choy, or little hatchet men."

On opium dens:

"The opium den was another thing that the Chinese resorted to because they had no other place to go. At that time nearly every store in Chinatown had an opium layout in the rear for their customers. All the Chinaman had to do was bring his opium. In those days the Chinese were allowed to smoke opium, provided they did not do so in the presence of a white man. If a white man was present it meant the arrest of all who were in the room at the time.

In the old days, at the corner of Washington Street and Spofford Alley, in a room right off the street, anyone could see Chinamen mixing old opium with new. That is, after opium is smoked the ashes drop down into the pipe in the bowl. This is scraped out with certain instruments and saved. It is then known as “Yen Shee,” and is later mixed with new opium. I have seen as many as 100 Chinamen smoking opium in a den in Chinatown. The opium smoke was sometimes so thick in those dens that the gas jets looked like small matches burning."

Links:

"Genthe's Photographs of San Francisco's Old Chinatown"

with text by John Kuo Wei Tchen

"Arnold Genthe's 'San Francisco Chinatown, 1895-1906'" (California Historical Society)

"San Francisco's Old Chinatown" (Chief Jesse Cook, 1931)

Chinese San Francisco, 1850-1943 by Yong Chen